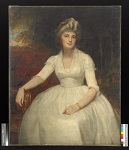

Sophia Dawson by Romney

A history of the Dawson family up to the end of the 19th century

This account has been extracted and summarised by Julian Scott from ‘History of the Dawson Family’, compiled by Mary Louisa Dawson, and ‘Letters of Lieut. Col. Dawson’ from South America and Canada. It shows the wide variety of historical influences in the family of Christopher Dawson and contains several fascinating eyewitness accounts of life in the 18th and 19th centuries – as well as an anecdote about Anne Boleyn.

The first Dawsons appear out of obscurity at Halton Gill in the parish of Arnecliffe, Yorkshire, in the 15th century, where they owned a fairly small amount of land, which they gradually expanded. In 1645 one Josias Dawson married the daughter and only child of William Foster of Langcliffe Hall, Settle and so came into possession of that property on the death of his father-in-law. This extension of their property through marriage was continued by the eldest son of said Josias Dawson, Christopher, educated at Giggleswick Grammar School. In 1673 he married Margaret, youngest daughter of Thomas Craven, of the High Hall, Appletreewick, who in turn was the great nephew of Sir William Craven, Lord Mayor of London. The Dawsons thus began to move in exalted circles.

In addition to his existing properties (Langcliffe, Appletreewick and the earlier ones) Christopher Dawson bought the Manor House of Hartlington and other property there in 1687. His second son, William, made a brilliant marriage, to Jane, daughter of Ambrose Pudsey, of Bolton Hall, High Sheriff of Yorkshire in 1683 and 1693. Only three years after their marriage, she died, and twelve years later he re-married into a Lancashire family named Marsden.

According to Mary Louisa Dawson, ‘William Dawson was a man of talent and literature who was a friend of Isaac Newton. It is said that Newton discovered the law of gravitation by seeing an apple fall in the garden at Langcliffe when on a visit to Major Dawson.’ (He was generally known as Major Dawson as he held a commission in the Militia).

In 1703 William Dawson and his mother (Margaret) bought a house at Settle, now known as the Folly. According to Mary Louisa Dawson, ‘It is a fine specimen of the domestic architecture of Yorkshire in the seventeenth century … Very possibly it may have served as a dower house for Margaret Dawson, née Craven… Major Dawson was Justice of the Peace for the West Riding; he lived to a good old age and died in 1762, aged 86, and was buried at Giggleswick. In the hall at Langcliffe is his portrait let into the panelling. It represents an aristocratic, somewhat haughty looking man, with flowing wig, with a full white neck cloth and a coat with braided fastenings.’

The next event of interest was the migration of the youngest son of Major William Dawson, another William (b.1723), to London, where he married Sarah, second daughter of Canon Balthazar Regis, Rector of Adisham and Chaplain to George I (and II). Sarah is described as having “something majestical about her”, as a portrait of her confirms. Canon Regis was an interesting person, a Huguenot, born at Chatenau, Dauphinée, France where his family owned large estates. But he was forced to flee at the age of seven on account of the family’s religion. He was educated at Lausanne and then at the University of Berlin, after which he went to Flanders to become Chaplain to a Swiss regiment. He finally settled in England where he attracted the attention of the Prince of Wales, later George II and was eventually made Chaplain to George I and later to George II. His second wife was Jeanne Aufrère, daughter of Rev. Antoine Aufrère, Marquis de Corville, by whom he had three daughters, Sarah (see above) being the second. He died in 1757 and was buried in the Cloisters of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor.

On the death of his father (Major Dawson), William Dawson became a wealthy man, what with his father’s property and the dowry of his mother. He therefore ‘removed from London to Richmond, and also had a house at Bath … the last but one at the top of Milsom Street’. Quite a lot of information is available on the life of this 18th century family, as a niece of William and Sarah went to live with them and kept a diary, of which the following contains some amusing extracts.

They went on a three months tour of Wales (the niece and Mr and Mrs Dawson). They found the inhabitants of Camarthen most unfriendly (‘it was impossible for strangers to be pleased with the behaviour of the townspeople’), but this may have had something to do with the following fact: ‘… the streets being narrow we pull’d down their Porches which projected out, as the coach passed; they then came out Like a Pack of Hounds, and set upon us, but the Coachman used to whip his Horses to get out of hearing of their abuse …’. This niece did have a good word to say for the Welsh harp playing which could be heard in the evening in almost every house, but soon returns to the attack: ‘The people are also furious in temper, we got ourselves much abused one day by disputing the price of a cake at the Pastry cooks. She said she knew the English very well, in short was so furious and behaved so rude we could never go to the shop again which was a great loss as the Pastry, Jellys and Custards were excellent.’

This couple had eight children, but only one survived, another William Dawson, to add to the confusion. Interestingly, he married another Huguenot descendant, in point of fact his second cousin, Sophia Aufrère, a noted society beauty, whose portrait was painted by Romney and Reynolds, amongst others. The Aufrères had been a noble family in France who, like the Regises, had been forced to flee because of their religion.

The mother of Sophia Aufrere was Anne Aufrère (née Norris) and her grandmother was Ann Norris, a severe looking lady whose portrait still survives. The Norrises were a Norfolk family who lived at Witton Park and Witchingham. An anecdote about the husband of Ann Norris (Sophia’s grandfather), John Norris, relates the following about his discovery and protection of the celebrated mathematician Parson: ‘Walking in his park at Witton, Mr Norris found the boy tending a cow,and at the same time working a problem, and struck by the lad’s ability he sent him to North Walsham School, and thence to Eton.’

William and Sophia Dawson had 9 children. The children had a French governess, the Comtesse de Montalembert, whose husband had been guillotined in the French revolution, so that she and her son had been ‘forced to fly their native land in an almost penniless condition’. The Dawsons lived at Windsor, and also in London, at 10 Hinde Street, Manchester Square. The house and estate at Windsor was called St Leonard’s Hill, which William bought on his father’s death in 1803, when he came into possession of a large fortune. The house there was the one known as “Sophia Lodge” and still exists in the grounds of Windsor Safari Park. In front of it now stands a model dinosaur and a boating lake.

An anecdote which illustrates the strength of character of Sophia Dawson goes as follows: ‘It is said that on one occasion, being at Windsor Castle on a Sunday, King George asked Mrs Dawson to play cards, but she refused, saying she never played cards on a Sunday. The rest of the company were amazed that anyone should dare to refuse a request of the King’s, and they predicted that Mrs Dawson would never again be invited to Windsor Castle. Nevertheless she was, and the King remarked to her, apropos of the card incident, “You are a good little woman, Mrs Dawson”.’

One of their daughters also had a brush with the King. ‘… about two years old, she was on the Terrace at Windsor Castle when George III and Queen Charlotte were walking there. The King stopped and took Caroline up in his arms, she was not in the least shy, and pointed out her red shoes to the King, who said “My dear, you must not be vain of dress.”’

On another occasion, ‘while attending the Court festivities down at the Pavilion in Brighton, the old Queen Charlotte was present, but being tired, sat down on a sofa in a dark corner in one of the rooms. Mrs [Sophia] Dawson, coming into the room with her daughters, went towards the sofa, and not seeing the Queen, who was ‘huddled up in the corner’, probably indulging in a nap, was about to sit down when one of her daughters cried out, “Mamma, Mamma! You are sitting on the Queen!”’

An interesting account survives of a ball given at their house in Manchester Square (from the Morning Post of July 2nd, 1818): ‘Mrs Dawson’s Ball, in Manchester Square, on Tuesday, was attended by upwards of two hundred fashionables. Refreshments of the choicest kinds were served in the Back Drawing-room and Library. Two rooms were appropriated for Quadrilles, a temporary bandstand for Coligni’s Band was judiciously arranged in the ante-room. The supper rooms were thrown open at half-past one, and a magnificent cold collation was served, consisting of the choicest fruits and Wines, Champagne – Claret – and French wines in abundance. After supper dancing was resumed with great spirit and kept up till five in the morning, when Tea and Coffee were served, and the party broke up highly delighted with their entertainment.’ (This is followed by a list of eminent guests including the Sicilian and Bavarian Ministers and a host of Earls, Lords, Ladies and Countesses).

The second son of the Dawsons, Henry, married Juliana Buxton, of a family claiming descent from Edward III. This family, however, had what it considered to be a skeleton in its closet, in the form of Sir Thomas Beevor, Juliana’s maternal grandfather. ‘He was a very eccentric man, of Socialistic and revolutionary tendencies, and wore the red cap of liberty, and liked to be called “Citizen Beevor”. This sort of thing was not at all pleasing to the loyal and Conservative Sir Robert Buxton, who forbad his family to have any intercourse with the Beevor family’. However, Sir Thomas had a very beautiful daughter and one of Sir Robert’s sons fell in love with her and, in spite of all opposition, the marriage came off and proved to be a happy one. This son, Robert, was a great friend of Pitt and attended his funeral. The funeral invitation still survives.

Henry and Juliana’s eldest son was another Henry, a soldier, who married Harriet Bainbrigge, daughter of Sir Philip Bainbrigge who fought in the Spanish Peninsula war with Wellington. The Bainbrigges traced their descent to Edward I and one of their ancestors, an MP, was committed to the Tower for his part in a debate on liberty of speech in 1587. He left an inscription there which still survived at least until the early 20th century and states ‘Vincet qui patitor. Ro. Bainbrigge.’

Henry’s son was Henry Philip Dawson, another soldier, who married Mary Louisa Bevan, the compiler of this family history. Her family, through marriage, represents the old Royalist family of Gwynne, whose pedigree, apparently, ‘begins with Adam and includes Old King Cole’. It is through one of these Gwynnes that a trinket belonging to Anne Boleyn came into the family. This Gwynne ‘was a Captain of the Guard at the Tower when Queen Anne Boleyn was beheaded. To him the unfortunate Queen gave a gold trinket, of beautiful Italian workmanship, in the form of a snake, saying, “snake it is, a snake it has proved to me.” It had been Henry VIII’s first present to her, and is still preserved in the Bevan family.’

Henry Philip Dawson inherited all the family’s estates in Yorkshire and in 1896 retired from the army with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel to live at Hartlington in Yorkshire.

He made some interesting journeys to South America and Canada, mostly for the purposes of scientific research. He was also with Kitchener during the Franco-German war.

In a letter from Panama, the following gives an idea of the adventurous life he had. The action takes place in Ecuador: ‘On 3rd November I started with an American engineer to see a new road that is being made to the coast. The first night we stopped at a Hacienda a few miles from Quito, and the next morning, crossing the Cordillera at a height of about 12,000 feet, we descended for the greater part of the day through the most beautiful scenery, palms, tree-ferns, orchids of a hundred different kinds, waterfalls, torrents and precipices, till after riding 30 miles we found the road had been carried away by a landslip …. About six miles beyond was the end of the road, where the workmen were busily engaged in blasting a ledge along the face of the precipice. We went on beyond this, where perhaps no white man had ever been before, but it was very hard work. Now we were clambering along the face of a precipice by the aid of creepers and roots, now skirting the edge of the torrent on stepping stones, and then balancing ourselves on a branch of a felled tree lying on a bottomless morass. Mosquitoes and other horrors attacked us vigorously, and we were in momentary expectation of being bitten by one of the numerous poisonous snakes that abound there. To add to the pleasures of our climb, the damp steamy heat was most oppressive … We escaped the vampire bats, which are very numerous, by sleeping in tents, and the fever, which had begun to make its appearance, by taking quinine …. The ride down was awful, and I wonder I did not break my neck. It was snowing or raining the whole time, and the latter part of the descent was extremely slippery. My horse was utterly unable to stop itself, and slid down the slopes at a tremendous pace, now coming down on its knees, now on its haunches, but luckily never rolling over. [At one point he has to dismount and] after a good deal of tugging I persuaded the horse to follow me, when down he came like a railway train, and I only escaped being knocked over by catching the reins as he came down on me, and sliding down the rest of the way holding on to the bridle. Such is riding in the Andes.’

It is truly amazing to see, amidst his evident love for the beauties of nature, a trigger-happiness with regard to any animal life that presents itself, a fact which only goes to show how mentalities change from one century to the next. ‘As I came along I saw two condors sitting on a crag about a hundred and fifty yards off, and by great good luck [not for the condor] succeeded in knocking one over with my revolver. I had a great chase over the rocks after it, but a second shot stopped it, and then I got my lasso over its head, and lowered it down the rocks into the path. I had to content myself with taking the wing-feathers as trophies, as I had no time to skin it and nothing to preserve the skin with. If I could only have got the skin I would have had a railway rug made of it, but it was not a full-grown bird, I should not think it was more than 9 or 10 feet across the wings.’

His travels across Canada, on the ‘Circumpolar Expedition to Fort Rae’, are of a similarly adventurous nature, and his descriptions of the Canadian landscape, with its great lakes, rapids and forests, as well his sightings of the Aurora, are very fine, punctuated by enthusiastic hunting references, such as the following: ‘From his account it seems it (Fort Rae) will be a delightful place – reindeer so plentiful that they sometimes walk into the fort, also wild geese and ptarmigan, so I shall have plenty of sport.’

One thing, perhaps, is lacking in all these accounts, and this is any mention of the feelings or personalities of the characters involved, beyond a merely superficial description (e.g. ‘They are pleasant people and Mrs. Bumpus lived for some time at Naples’ – from Lieut. Col. Dawson’s letters). I wonder whether this is merely due to the brevity and historical nature of the account, or whether the people of those times did not mention such things.

Henry Philip Dawson and Mary Louisa Bevan had two children – Christopher Dawson and his sister Gwendoline. The rest is history…